In this lab, the nslookup utility is used together with Wireshark to investigate the DNS protocol. It also used a web browser (in this case, Firefox) to gain insights on how the DNS protocol is used in real-world scenarios.

nslookup

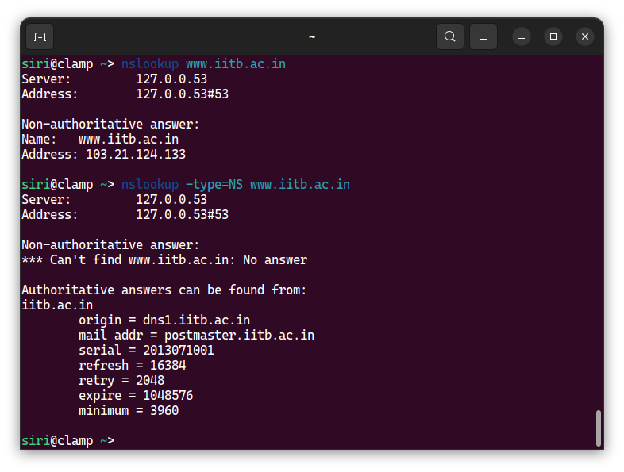

The figure above shows nslookup’s output when run on the web server of the Indian Institute of Technology in Bombay, India. Without any options set, nslookup returns the IP address of the requested domain, which is 103.21.124.33. It is also worth noting that the answer came from a non-authoritative server, which means that the result came from a cache. In this case, it came from my computer’s local cache (127.0.0.1).

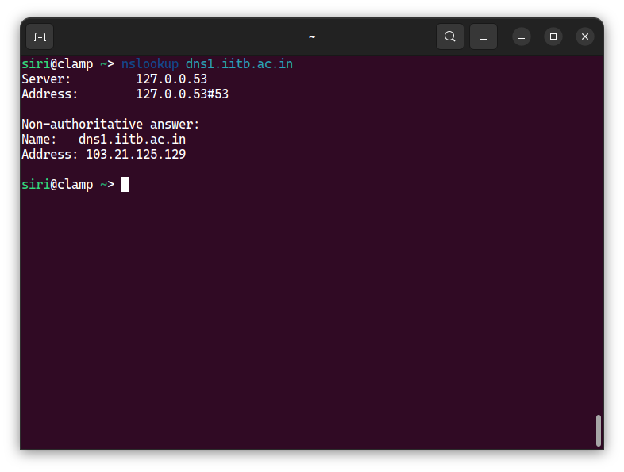

When the command is run with the option -type=NS, nslookup finds the authoritative name server for the given domain and it can be determined from the output that this server is dns1.iitb.ac.in. Running nslookup on the mentioned server gives its IP address, which is 103.21.125.129 at this moment.

The DNS cache on your computer

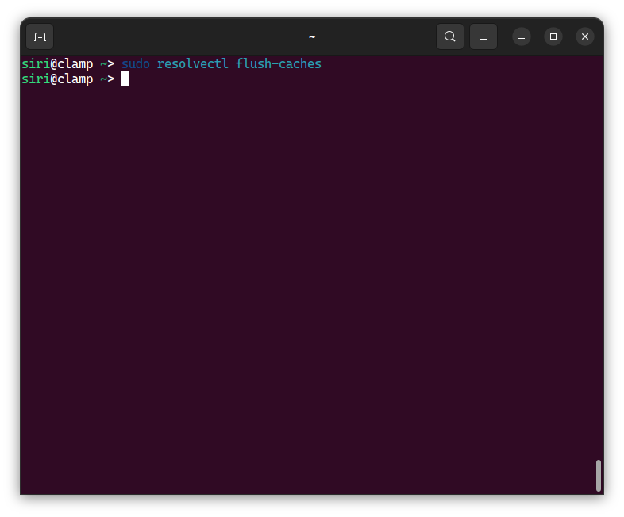

To prepare for the next activities of the lab, the DNS cache is cleared with the corresponding command for Ubuntu 24.04.

Tracing DNS with Wireshark

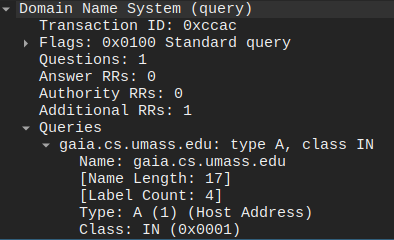

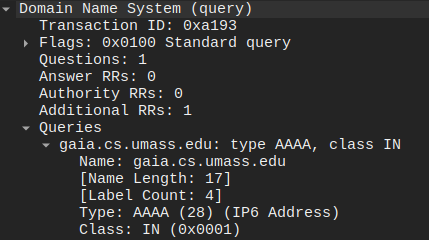

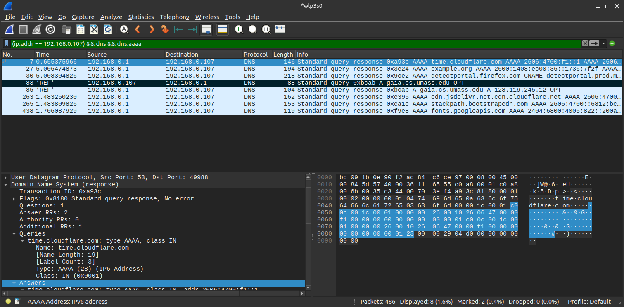

For this part of the lab, Wireshark was used to capture the DNS requests that may be sent out by a web browser upon first connection to a certain website. In this case, gaia.cs.umass.edu was used as an example.

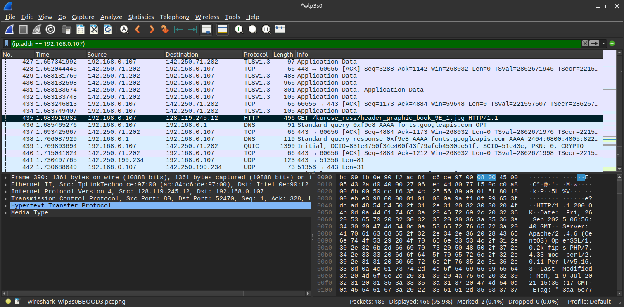

The above screenshot shows that the initial DNS queries were packet nos. 83 and 87 and that they were sent over UDP. The response — which is also in UDP — bears the packet nos. 85 and 91 (for IPv4 and IPv6, respectively) and comes about 281ms after the query was sent. Both packets were sent in communication with the default DNS server of the laptop which is the router (at 192.168.0.1).

Inspecting the DNS queries reveals that the first query asked for an A record, which is for an IPv4 address. This is immediately followed by the next query, which requested an AAAA record, which corresponds to an IPv6 address.

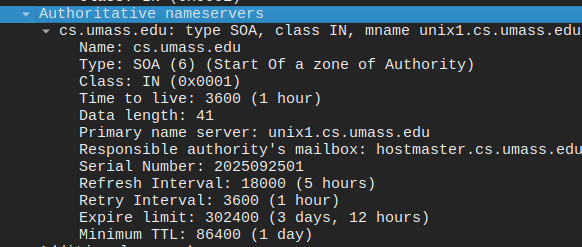

From the above observations, it can be inferred that the answers arrived in the same sequence the queries were sent out. This proved to be the case, with the A query returning with one question and its answer: the IPv4 address. However, the AAAA query only returned the authoritative nameservers for the domain name. While outside the scope of this lab, it can be hypothesized that this is because IPv6 is disabled on the user’s computer and/or router.

Going further, the HTTP request (packet no. 96) for the mentioned site comes 561ms after the answer to the DNS query was received. Then, the object /kurose_ross/header_graphic_book_9E_2.jpg was requested by the browser and there is no DNS query corresponding to this object. This indicates that the IP address was cached by the browser, and for this short period of time, further DNS queries do not need to be made as they will be redundant. The below screenshot shows that only the initial queries were needed to load everything from gaia.cs.umass.edu .

Next, the same requests were made using nslookup.

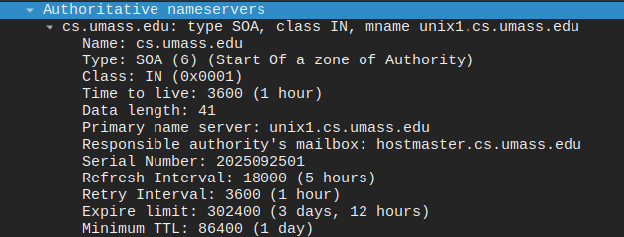

From the above screenshot, it can be seen that the DNS query message for the A record comes from port 42074 and into port 53 of the DNS server, which is the local router (192.168.0.1). Similarly, the AAAA and NS queries go into port 53 of the server, but it comes from ports 60870 and 60923 respectively.

There are a few differences between the queries and the responses. Queries only contain questions, while responses contain both the questions and the answers corresponding to each question. In this case, the computer received one answer per query.

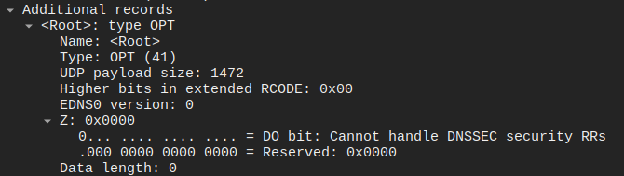

For the NS query, it returned the details of the authoritative nameserver such as the name, type, class, and the time to live. Lastly for all packets (queries or responses), there’s an additional record that contains 0 bytes.