This blog post contains answers from Kurose's Wireshark Lab on TCP. I highly recommend that you follow along as well by going to the original lab exercise!

This laboratory exercise explored the behavior of TCP by analyzing a trace of the TCP segments sent and received in transferring a 150 KB file (containing the text of Lewis Carrol's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland) from a computer to a remote server. Analyzed as well is TCP's use of sequence and acknowledgment numbers for providing reliable data transfer, and congestion and flow control mechanisms to minimize dropped packets due to queuing losses. The performance of TCP was also investigated in terms of throughput and round-trip time.

Capturing a bulk TCP transfer from your computer to a remote server

To perform this laboratory exercise, Wireshark was used to capture the TCP segments.

Before performing the laboratory exercise, the upload page (shown above) was loaded on the computer. The sample file was downloaded as well. The setup can be done while Wireshark is set to capture packets, but it was done beforehand as the exercise is focused on the upload of the sample file. This made sifting through the packets much simpler and clearer.

Next, Wireshark was set to capture packets, and the sample file was uploaded using the instructions found on the upload page. If everything was done correctly, the page below should show up:

After this, the packet capture was stopped. In the next sections, the trace will be analyzed to understand how TCP works.

A first look at the capture trace

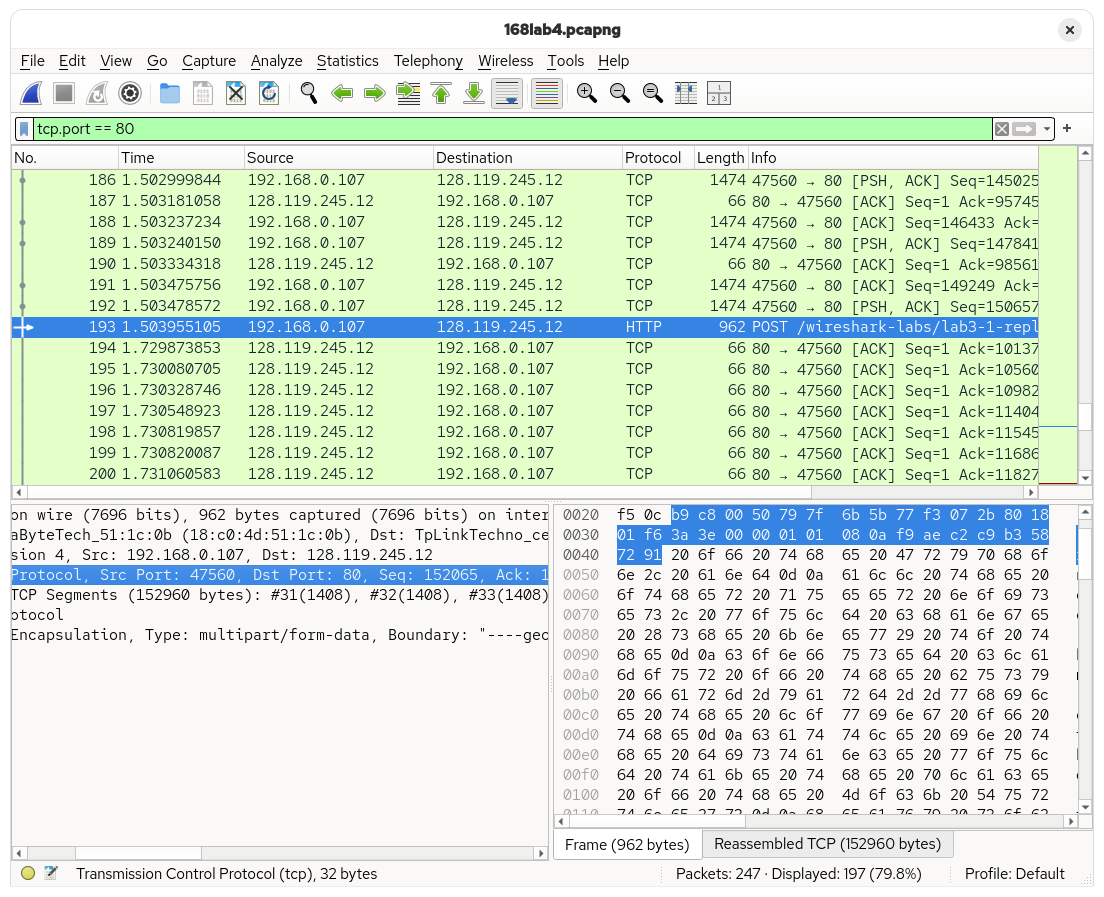

The POST request from the upload was found in the capture trace. It can be seen that the request came from the local computer (192.168.0.107) to the remote server (128.119.245.12). The connection used a local port of 47560 to communicate with the remote server, which is on port 80.

Due to NAT, the public IP address seen by the server is not captured by the trace.

TCP basics

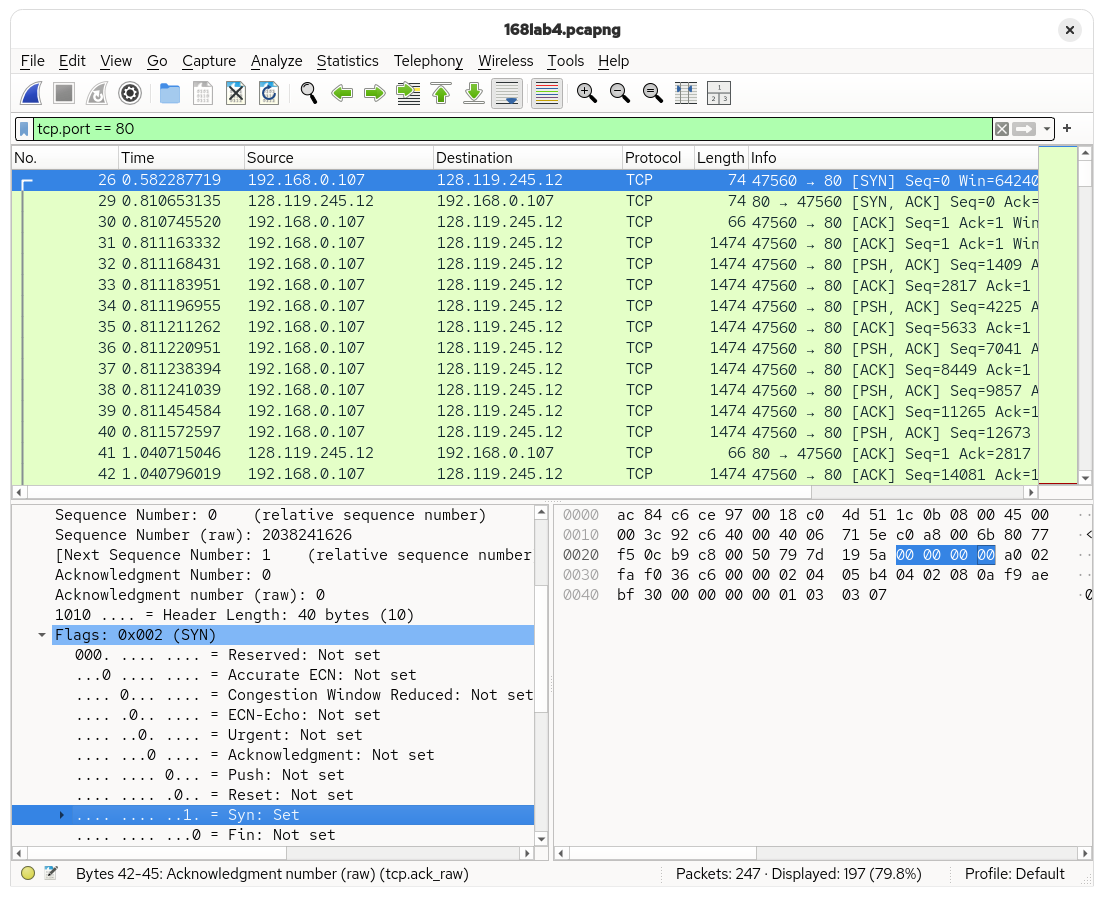

Every TCP connection starts with a SYN segment. This does two things:

- It indicates that the device that sent the segment (the client, in this case) wants to establish a TCP connection with the receiver (the server).

- It indicates what sequence number the connection should start with. It also synchronizes — hence the name

SYN— sequence numbers between the two participants. In this case, the sequence number is2038241626.

After sending a SYN, the server will then respond with a SYN+ACK. Note that this is not two segments sent one after the other, rather a single segment where both the SYNchronize and ACKnowledgment bits are set to 1. Notice that the server used the same sequence number indicated by the client in the SYN packet it sent.

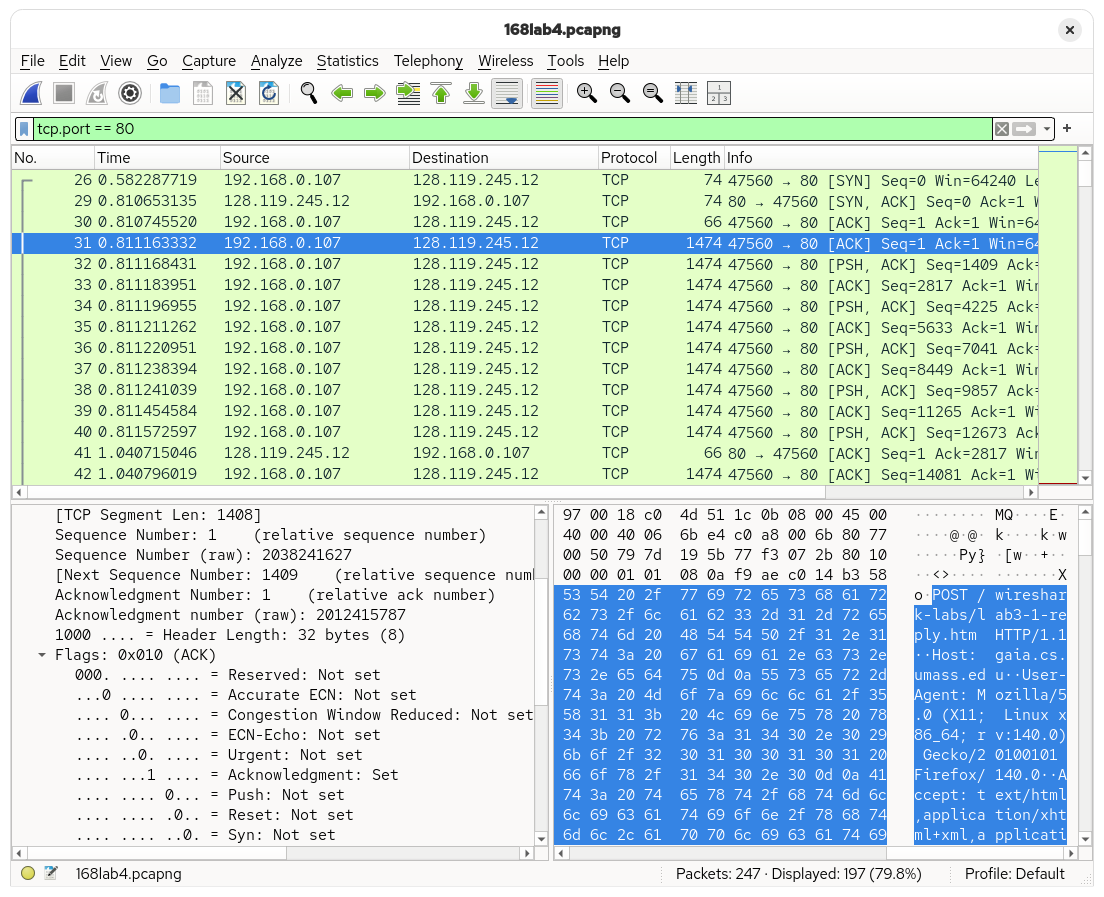

After the SYN+ACK segment, the client sends an ACK segment indicating that it has received the SYN+ACK sent by the server and that the connection was successfully established.

Before proceeding to the next section, it is also worth noting that TCP has a feature called SACK or Selective Acknowledgment. This allows both the server and the client to send a list of received segments to each other rather than sending an ACK for each packet received by either. This prevents the server from re-transmitting data that has been received successfully given the different delays that may occur in the network (particularly, the propagation delay). Ultimately, the SACK feature was not used in this connection.

Once the TCP connection was established, data can be exchanged between the server and the client. This is apparent in the next segment, which already contains the beginning of the HTTP POST message. Overall, it took about 229 ms for the first data-containing segment to be sent, which is equivalent to 1 RTT (round-trip time). The second data-carrying segment is also almost the same, taking 230 ms to be acknowledged.

Speaking of RTT, TCP also estimates the RTT of the next segment to figure out the right time to wait for an ACK before it can consider the segment as "lost" and attempt to re-transmit. This is done using the following formula:

\[ \text{EstimatedRTT} = (1 - \alpha{}) \cdot \text{EstimatedRTT} + \alpha{} \cdot \text{SampleRTT} \]

The receiver (the server, in this case) also indicates how much space is available in its buffer to receive incoming segments, using the window size and the window scaling factor to do so. The sender will throttle its transmission rate when the buffer space available becomes too small to send packets at the current rate. The window size and the window scaling factor for the first four segments is shown below:

| Segment | Window Size | Window Scaling Factor | Available buffer space |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 502 | 128 | 64256 |

| 2 | 502 | 128 | 64256 |

| 3 | 502 | 128 | 64256 |

| 4 | 502 | 128 | 64256 |

In this case, the sender is not throttled.

| ACK | Sequence Number | Difference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| 2817 | 2816 | |

| 5633 | 2817 | |

| 7041 | 1408 | |

| 8449 | 1408 | |

| 11265 | 2816 | |

| 12673 | 1408 | |

| 14081 | 1408 | |

| 15489 | 1408 | |

| 16897 | 1408 |

It can be seen that ACKs occur every 1408 bytes or so, which is the size of a packet excluding all the header bytes.

Overall, measuring from the time the first segment was sent to the time the ACK for the last segment was received, the transfer took 922ms. Given that the whole file is 153kB, the average rate of transmission is 166 kB/s.

TCP congestion control in action

This section aims to analyze the TCP congestion control algorithm.

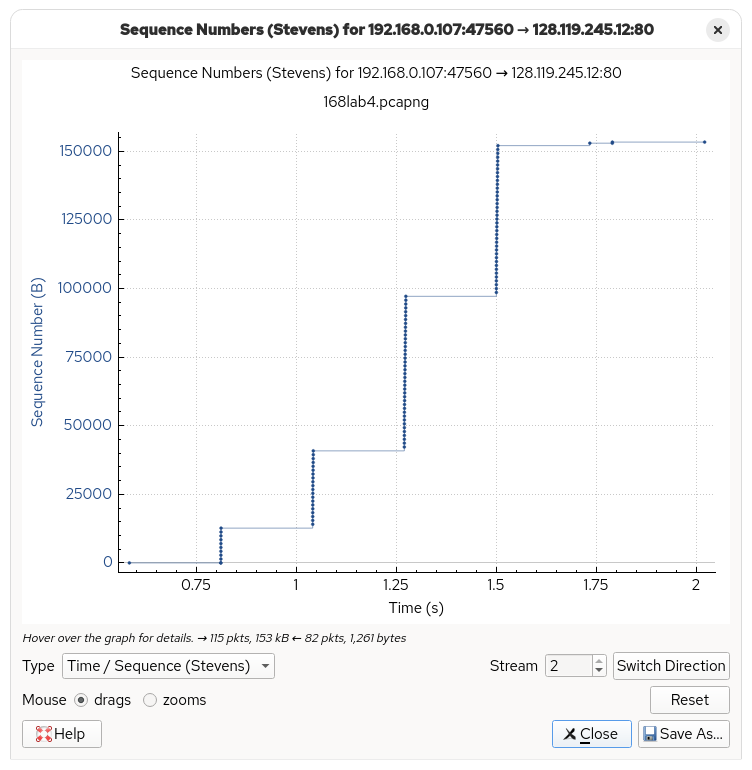

The connection seems to be in the slow start phase the whole time as the rate of segments being sent is increasing exponentially. We do not know if the last time segment (around 1.5s) means that the network is in congestion avoidance, as the transmission has already ended and there is no more data left to be sent. In addition, there is an interval of around 228-229.4ms between the “fleets”. This suggests that before sending more packets, the client waits for approximately one RTT.

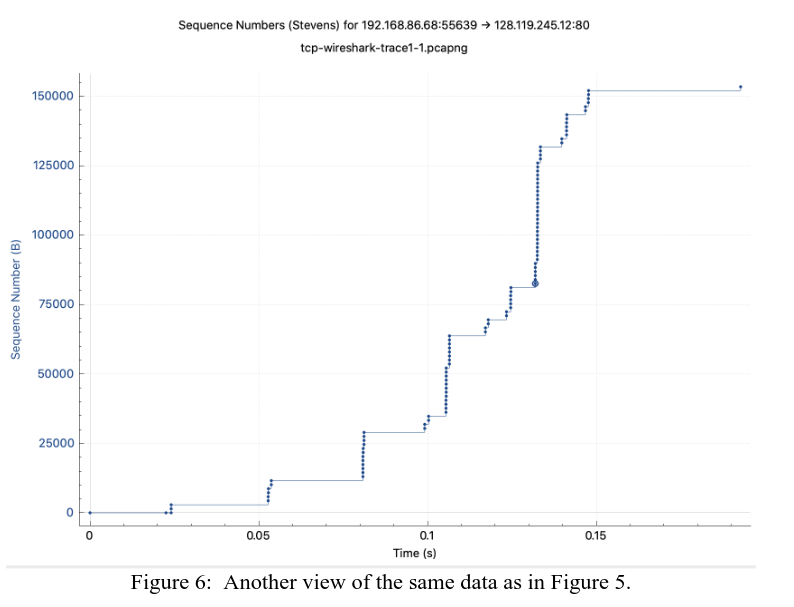

In contrast, here is the packet trace by Kurose, which sees the connection enter a slow start state multiple times.

Conclusion

Overall, the TCP Wireshark Lab gave me an insight on how TCP works, if only through the lens of a packet trace. I would definitely love to take a look at a TCP implementation and see how packets get reassembled and how the data gets sent to the application layer.